Please Note: This article

reproduces historic barrel browning recipes that contain

toxic ingredients. They are not to be

attempted and

are provided here for academic purposes only.

From Bright Steel to Brown:

The Colour of British Musket Barrels, 1755-1865

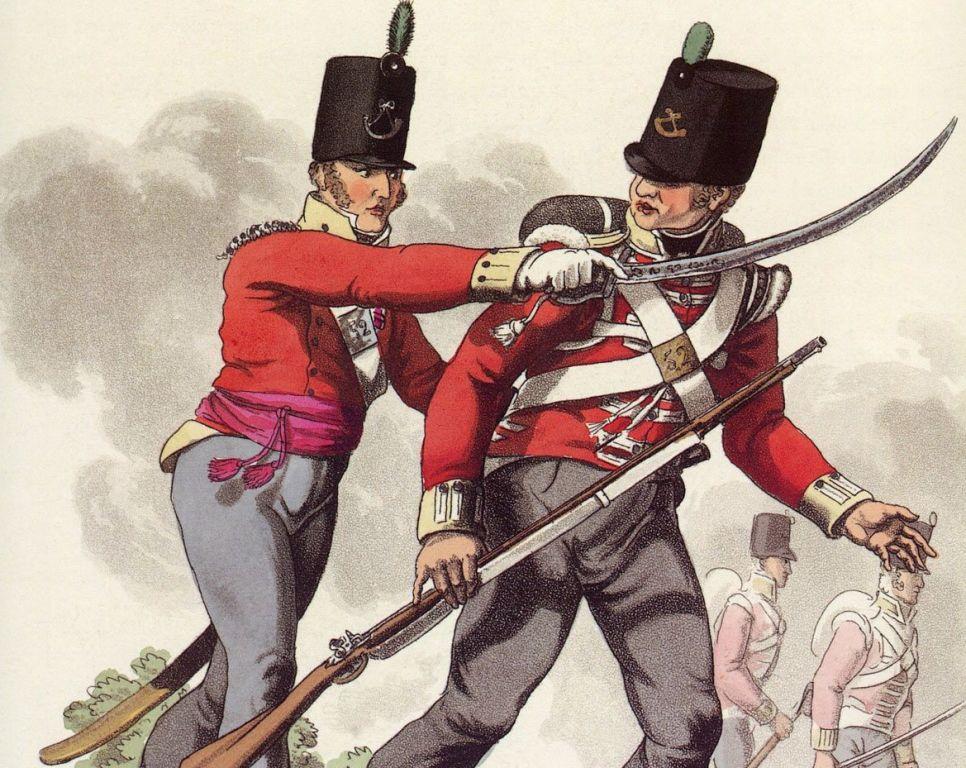

Detail showing a

British Grenadier Company with polished Short Land Brown Bess muskets.

Reproduction of that musket found here.

From The Death of Major Peirson, 1781 by John Singleton Copley

(painted in 1783)

While sportsmen had started browning their musket

barrels for hunting since the middle of the 18th century, muskets issued to

British regulars prior to the American Revolution

were expected to be brightly polished. Cuthbertson in 1768, writing on

the British Army considered the polished musket as a sign of pride

and profession.

Orders for the Nottinghamshire Marksman in 1778

highlighted its importance:

"..Such

being the importance of his Arms, no wonder that a soldier should shew his

attachment to his Firelock, by keeping it as bright as the Sun, and looking

upon it with a kind of veneration. A glittering Firelock is a prime ornament

of a Soldier and gives to every movement an appearance of double Life and

Spirit."

In some

instances bright arms had unexpected results.

During the American

Revolution just before the Battle of Guildford Courthouse, the American

General Lee was thrown from his startled

mount caused by the sun reflecting off the bright arms of

the opposing British troops.1 The polishing of the brown bess musket by British troops bordered on

obsessive compulsive. In 1776 Lord Townshend saw the raising cost of

polishing arms as extravagant: "The great expenditure of arms is [due]

to the unnecessary high polish, and injudicious manner in which some

Regiments treat them." The damage to the

barrels was significant. For example, in 1775 the arms of the 62nd

Regiment of Foot were reported to "have been so abus'd to keep them

bright, that there is not the appearance of the Kings mark." At the opening of the American Revolution,

the idea of browning barrels was considered by the British Ordnance, but

was rejected. 2

In his 1786 painting of the Death of General Montgomery

in the Attack on Quebec (1775), John Trumbull

suggests American soldiers also polished their muskets. Appears to be the

Long Land Brown Bess Musket.

Replica of that brown bess found here.

The preference for bright barrels

continued amongst line regiments throughout the Napoleonic Wars.

James wrote in his

Military Dictionary in 1805:

"the private soldier familiarly calls his firelock

brown bess; although the term is little applicable to the weapon, considering that it is

absurdly polished in almost every Regiment in the British Army."

One soldier,

Shadrack Byfield of the 41st Regiment, used this to identify friend from foe in the night

after the capture of Fort Niagara in 1813: "A short time after, we saw another man,

with polished arms, by which I knew he must be one of our men...He belonged to the

Royals."

The most common substances used in the 18th

century to clean the barrel was brick dust or emery powder mixed with sweet

oil (olive oil). One technique was to glue emery to a flat leather

covered deal wood stick and the scrub the barrels clean while applying oil

and emery or brick dust during the process.

After cleaning, the soldier then buffed the barrel to a high

polished state by burnishing it with his ramrod or rubbing it with a

wooden buffing stick. By the 1780s, crocus martis powder (jeweller's

rouge), was applied with a piece of clean leather, was used in the polishing

step producing a mirror finish. Soldiers would purchase crocus

privately and were compensated with an allotment of "crocus money" from the

army.

The obsession with maintaining a mirror finish

on the barrel did have a negative impact on its state.

For example,

in 1775, the 62nd Regiment's arms were reported as being "so Abus'd

to keep them bright, that there is not the least appearance of the Kings

mark".3

Other regiments

during the Napoleonic wars reported weak and worn barrels.

Efforts were made by army officials to deter this wear - caused mostly by

the practice of burnishing.

In 1795 the 43rd Regiment ordered:

"The men

must keep their arms... in the highest possible order with respect to

polish and cleanliness.... Every man must be supplied with a buff-stick

and other necessary articles for the purpose, and any man caught

polishing his barrel with his ramrod, or piece of iron, will be punished

for it."

However as

illustrated below these orders were mostly ignored.

In addition to wear, bright barrels had other disadvantages.

William Henry in his manual

A Media Plan for Military Animation at Fort George quoted an

interesting document on the subject.

In 1812, the colonel of the 102nd Regiment

ordered muskets of the regiment to be browned. An inspecting officer order the colonel to

submit a written explanation on why had done this.

His reasons for this were as

follows:

1. There was no regulation

against it.

2. The barrels could be made bright again with sand paper.

3. An order against burnishing the arms with the ramrods was seldom obeyed by other

Regiments.

Thus, if the 102nd (who presumably did not burnish their arms in

compliance with the order) were compared to other Regiments their arms would appear dirty,

thus hurting the pride of the 102nd.

4. Browning preserves the arms and they are cleaned with bees wax once or twice

every six months, thus, preventing rust and making it unnecessary to remove the barrel as

is so frequently done now.

5. The dazzle of bright arms prevents aim being taken in the sun - proof of this is

that brown barrels are universally used by sportsmen.

The colonel concluded his

explanation by stating that the men were pleased with the browning and that it helped to

get recruits from the Militia.

However the 102nd was far from the first to carry browned or "black" muskets in

the British service.

Over 50 years earlier in 1757 a less expensive brown bess was

introduced for Marine and Militia service that was not required to be polished.

The

finish for these muskets was referred to as "black" (likely

japanned).

British issue rifles from the first in 1776 seemed to have been

always browned.

The regulations for the Experimental Rifle Corps (later 95th

Regiment) in 1803 cautioned its men about not injuring the browning.

This echoed in

Barber's work in 1803: "The outside of the barrel should never be rubbed with

anything than can impair the brown."

But did regular regiments brown their

muskets prior to 1812?

The American Revolution had brought a number of innovations

and improvements to the British Army.

One area that saw a lot of activity was Light

Infantry.

Each regular regiment had a light company attached to it.

It appears

that these light companies were issued with black or browned muskets was early as

1787.

In an inspection return of the 38th Regiment of that year under the

category

"arms" it was noted : "the Light Infantry Company have the new black

barrels."

Sir John Moore's 52nd Regiment of Light Infantry carrying

the browned-barrelled

New Land pattern Brown Bess Musket.

Reproduction of musket can be

found here.

During the Napoleonic Wars a number of regiments were designated entirely light

infantry.

The first were the 43rd and 52nd Regiments followed by the 51st, 68th,

71st and 85th Regiments along with a number of Fencible corps.

All were influenced

by the innovations of the 52nd's colonel, Sir John Moore.

Moore altered the light

infantry drill was altered to be more efficient.

For example instead of making ready

at the recover position, Moore had his men come back to the prime position to make

ready.

This change allowed greater accuracy when presenting because the soldier no

longer had to struggle against the weight of a falling musket from the recover position

when presenting and aiming.

This innovation (and others) were adopted by the

other light infantry regiments and by 1812 the light company of at least one line

regiment, the 7th Regiment.

This practice was formally adopted for the entire army

in 1828.

Armed with the New Land Musket, the light infantry regiments shared in another

practice: browning barrels.

By the

end of the Napoleonic Wars, the tide had turned against bright steel.

On 22nd June

1815, four days after the Battle of Waterloo, orders were issued with instructions from

Horse Guards for all British Army muskets to be browned.

For those who are

interested in the browning process adopted by the British the following are

the instructions for browning issued in 1815 along with additional instructions a few

months later.

The browning process is controlled rusting by acids, which today we call

rust bluing. These orders are taken from General Regulations and Orders for the

Army, 1811 (revised 1816):

"Instructions for

Browning Gun Barrels

The following Ingredients:

Nitric Acid

1/2 ounce

Sweet Spirit of

1/2 ditto.

[toxic

ethyl nitrite]

Spirits of Wine

1 ditto.

[ethyl alcohol]

Blue Vitriol

2 ditto [copper sulfate]

Tincture of Steel

1 ditto.

[alcoholic solution of the

chloride of iron]

are to be mixed together,

the vitriol having been previously dissolved in a sufficient quantity of water to make

with the other ingredients, one quart of mixture.

Previous to commencing the

operation of Browning the Barrel, it is necessary that it be well cleaned from all

greasiness and other impurities, and that a plug of wood be put into its muzzle, and the

vent well stopped; the mixture is then to be applied with a clean sponge or rag, taking

care that every part of the Barrel be covered with the mixture, which must then be exposed

to the air for twenty-four hours, after which exposure the Barrel must be rubbed with a

hard brush and rag, to remove the oxid from the surface. This operation must be performed

a second and a third time (if necessary), by which the Barrel will be made of a perfectly

brown colour: it must then be carefully brushed and wiped, and immersed in boiling water,

in which a small quantity of alkaline matter has been put, in order that the action of the

Acid upon the Barrel may be destroyed, and the impregnation of the water by the Acid

neutralized.

The Barrel when taken from

the Water must, after being perfectly dry, be rubbed smooth with a burnisher of hard wood,

and then heated to about the temperature of boiling water; it then will be ready to

receive a varnish made of the following materials;

Spirits of Wine

1 Quart [ethyl alcohol]

Dragon's Blood powder 3 Drams

[bright red resin used in

varnish]

Shellac bruised

1 Ounce

and after the varnish is

perfectly dry upon the Barrel it must be rubbed with the burnisher to give it a smooth and

glossy appearance.

To repair and retain the

Brown upon Barrels.

When the Barrel is much

rubbed from use, a little vitriolic Acid may be applied to it, and then it must receive

the treatment that Barrels undergo in Browning, care being taken to deaden the action of

the Acid by means of boiling water.

When Brown Barrels are in

constant use tile Brown might be continually kept perfect by means of the application of

vinegar, which should remain upon the surface for a Day, and then be washed well with

boiling water.

If this operation be

repeated monthly, a Barrel which has been properly Browned in the first instance will

continue in a perfect state for many years.

Office of Ordnance,

16th July, 1815.

Additional Instructions for

Browning Arms.

The Barrel, with the Socket

and Neck of the Bayonet only, are to be Browned; they should he rubbed over either with a

fine File, or with coarse Emery Paper, previous to their receiving the Browning Liquid, in

order that its effect may be the greater.

In removing the Oxid from

the Surface of the Barrel, &c a Steel Scratch Brush will be found more

effectual than the hard Hair Brush; the use of the Steel Scratch Brush is

therefore to be

adopted. This part of the operation must be done with great care, as upon it depends the

proper Browning of the Barrel.

In moist Weather the operation of

Browning must be performed in as dry a situation as possible,

for humidity upon the Oxid weakens its effect, which must be

carefully guarded against.

The Locks are on no account

to be made of the Hardening Colour, as the repetition of the operation of hardening has a

very injurious tendency.

Office of Ordnance,

29th December, 1815"

It is important to emphasize that just the

barrel and the socket part of the bayonet were browned and blued. The

lock and ramrod remained bright steel. The approach of browning only

the barrel remained unchanged through the rest of the history of British

muzzleloading muskets and rifles, including the four models of the pattern

1853 Enfield. The browning process was first done at the factory but

then needed to be redone every two years by regiment's armourer.

The Big Room at the Enfield Rifle Factory in 1861 There

was a separate Browning-room.

As a comparison with the original 1815 method,

the British Army modified the browning process in 1839. The recipe changed

in 1859 removing blue vitriol (copper sulphate). This may have been

mistake. In 1860 recipe changed again and a but the process

remained unaltered to the end of the production of the pattern 1853 Enfield

Rifle. Both the 1839 and the 1859 recipes are shown:

Instructions for Browning Gun Barrels

The following ingredients for the

browning of arms are to be mixed, and dissolved in one gallon of

soft water, viz:

|

[1839]

1 1/2 ounces of Spirits of wine

[ethyl alcohol]

1 1/2 ounces of Tincture of steel

[alcoholic of the chloride of

iron]

1/2 ounces of Corrosive sublimate

[toxic mercury chloride]

1 1/2 ounces of Sweet spirits of nitre

[toxic

ethyl nitrite]

1 ounce of blue vitriol

[toxic

copper sulfate]

3 ounces of Nitric acid

(are to be mixed and dissolved in one quart of soft water

[rain water] ) |

[1859]

6 ounces of Spirits of wine

6 ounces of Tincture of steel

2 ounces of Corrosive sublimate

6 ounces of Sweet spirits of nitre

3 ounces of Nitric acid

(the mixture is to be kept in glass, not in earthenware

bottles) |

Previous to commencing the operation of

browning, it is necessary that the barrel should be made quite

bright with emery or a fine smooth file (but not burnished), after

which it must be carefully cleaned from all greasiness; a small

quantity of pounded lime rubbed well over every part of the barrel

is best for this purpose: a plug of wood is then to be put into the

nose of the barrel and the mixture applied to every part with a

clean sponge or rag. The barrel is then to be exposed to the air for

twenty four hours: after which it is to be well rubbed over with a

Steel scratch-card or Scratch-brush, until the rust is

entirely removed; the mixture may then be applied again, as before

and in a few hours the barrel will be sufficiently corroded for the

operation of scratch brushing to be repeated. The same process of

scratching off the rust and applying the mixture is to be repeated

twice or three times a day for four or five days by which the barrel

will be made of a very dark brown colour.

The barrel is then to be exposed to the

air in a warm room for twelve hours, after which time it is to be

well rubbed over with a hard hair brush, or armourer's brush, until

the rust is entirely removed. The mixture is then to be applied

again in the same manner as before, and in six hours the barrel will

be sufficiently corroded for the operation of scratch-brushing. The

process of scratching off the rust and applying the mixture is to be

repeated twice or three times a day for four or five days by which

time the barrel will be of a dark brown colour. The rust which is

raised by each successive application of the mixture is always to be

removed at first with the hair brush previously to using the scratch

card as the latter is otherwise found to remove the browning. The

operation of scratch carding is only to commence after the second

application of the mixture.

When the barrel is sufficiently browned

and the rust has been carefully removed it is to be placed in

boiling water for three or four minutes in order that the action of

the acid mixture may be destroyed and the rust prevented from rising

again. The barrel while warm is to be rubbed over with sweet oil or

common olive oil. The operation for browning should be conducted in

a dry and warm room; a temperature of about 70 degrees is the most

favourable. The locks are on no account to be made of the hardening

colour as the repetition of the operation of hardening has a very

injurious tendency.

Boring and Grinding Gun Barrels, 1858

In December 1860 the process used by Infantry

regiments to re-brown their Enfield rifle muskets was further refined:

"WO. Circular. 653. 11 Dec. 1860

Browning recipe -

Tincture of steel 4 ounces

Sweet spirits of niture 4 ounces

Spirits of wine 3 ounces

Nitric acid 2 ounces (May 1862 order: concentrated

spec. grav. 1.42)

Blue Vitriol 1 ounces

Rain water 2 quarts

In mixing the ingredients the blue

vitriol should be dissolved in cold rain water, and the other

ingredients subsequently added.

The mixuture must be kept in a cool place, in glass bottles well

stoppered, as it will soon lose its virtue if kep in earthenware

jars, or if the stoppers do not fit well.

Directions for Browning

Before the mixture is applied to the

barrel the nipple hole should be carefully stopped up, to

prevent any water or browning mixture getting inside, and the

muzzle should also be stopped with a peg, made of pine or deal,

about 12 inches long, 4 inches of which are to be inserted in

the barrel; the remainder will serve as a handle to the workmen.

1st. Coat the barrels with wet lime,

clean with dry lime, and brush and wipe them with coarse linen

cloth; coat them with the mixture with sponge, and then let them

stand in the drying-room 12 hours in 60 dgrees heat.

2nd. Scratch them with wire-card,

after which let them stand one hour , coat them and stand them

in the drying-room six hours.

3rd. Scratch them with wire-card,

let them stand one hour, coat them and stand them in the

drying-room six hours.

4th. Scratch them with wire-card,

let them stand one hour, coat them and stand them in the

drying-room six hours, after which immerse them in boiling

water, every one being in the copper five minutes; then let them

stand one hour, coat them and stand them in the drying-room six

hours.

5th. Scratch them with wire-card,

let them stand one hour, coat them and stand them in the

drying-room six hours.

6th. Scratch them with wire-card,

let them stand one hour, coat them and stand them in the

drying-room six hours.

7th. Immerse them in boiling water,

after which scratch them with wire-card.

8th Immerse them in boiling water,

finish them with wire-card, and then oil them.

It will be observed that the time

allowed for drying is in the first instance 12 hours, and the

subsequent stages six hours. The barrels will generally be

dry in this time, but as the atmosphere his a great effect upon

the acids of which the browning mixture is composed this will

not be invariably the case. It can be easily ascertained

whether the barrels are dry or not by applying the steel scratch

card, when, if dry, the rust will fly off quickly, but if not

dry the rust will adhere firmly and the barrel will have a

streaky appearance.

Fine and dry weather should

invariably be chosen for the operation of browning, as far as

exigencies of the service will permit.

In consequence of the mixture for

browning arms supplied from England having been found liable to

deteriorate by fermentation on its voyage to distant colonies,

the ingredients for making the browning liquid are to be

furnished to foreign stations in an unmixed state. No

corrosive sublimate or other materials but those specificed in

the instructions will be supplied or are to be used in browning

arms.

The bands of rifle muskets are to be

blued and not browned."

Of course more than the browning solution was

need to brown the barrels. In 1864 items need included:

Bone dust

Borax for soldering

Brass spelter

Browning mixture

Brushes, hard

Charcoal

Emery flour (size 80 holes)

Emery cloth

Glass paper, fine No. 1 1/2

Glass paper, coarse No. 2

Glue

Oil, Rangoon

Plugs, wood for holding barrels

Rosin

Sal Ammoniac

Scalding trough, pattern at Pimlico

Scratch card (by the yard)

Sheeting, old

Sponges

Tin, bar, for soldiering

Tow

It is interesting to point out that throughout

all these instructions from 1815, it is specifically noted that the locks

were not to be browned and they were not "made of the hardening colour."

At the factory the lock plates and hammers were case hardened to a dull

grey. However the soldiers would have polished this off fairly soon

after being used the new musket. Army officials restricted regimental

armourers from re-hardening them. Explained in 1864: "The lock-plates

are on no account to have the hardening colour renewed upon them, as the

process has a very injurious tendency in destroying the texture of the

case-hardened iron of which they are made."

Another point of confusion is the bluing of

Pattern 1853 barrels. The browning processes listed above we would

call today rust bluing. When the acid is washed off with boiling

water, a dark bluish black surface is left. One 1858 treatise

recommended after the rusting acids are stopped by the boiling water, the

barrel should be put in cold water to maximize the bluish black surface.

Actual chemically bluing of gun barrels started in 1880s. The

Bluing mentioned for the barrel bands of the pattern 1853 Enfield is simply

heat treating of iron to a blue colour.

Warning:

Because many of the ingredients of the above browning recipes are

of toxic and dangerous, it is NOT recommended to reproduce these

processes. This information is provided here for only academic purposes.

__________________________________________

1 Special thanks to Jay Callaham for this reference.

2 John Rees, "The Care and Cleaning of Firelocks in the 18th Century"

The Brigade Dispatch, vol. XXII no. 2 (Summer 1991)

3 Special thanks to Eric Schnitzer for this reference.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bennett Cuthbertson, A System

for the Compleat Interior Management and Oeconomy of a Battalion of

Infantry. (London, 1768).

George Sutton, Standing Orders

and Instructions to the Nottingham Regiment of Marksmen. (Hull, 1778).

Henry Trenchard, The Private

Soldier's and Militia Man's Friend. (London, 1786). 1804 Edition

also consulted.

Horse Guards, General

Regulations and Orders for the Army. (London, 1816)

-----------------, Standing

Orders of the 43rd Regiment of Foot (n.p, 1795).

Shadrack Byfield, A Narrative of

the Light Company Soldier's Service in the 41st Regiment of Foot during

the Late American War. (Brantford, 1840)

William Greener, Gunnery in 1858.

(London, 1858)

Frederick Augustus Griffiths,

The Artillerist's Manual and British Soldier's Compendium. (London)

Editions Compared: 1839,1847,1856,1859 and 1862.

War Office, Royal Warrants,

Circulars, General Orders, and Memoranda... August 1856 to July 1864

(Glasgow, 1864)

Martin Petrie, Equipment of

Infantry. (London, 1865)

William Henry,

A Media Plan for Military Animation at Fort George. Parks

Canada, 1979.

|

Author Robert Henderson enjoys unearthing and

telling stories of military valour, heritage, and sacrifice

from across the globe. Lest we forget.

|

MORE FREE ARTICLES

like this one can be found here:

|