WHEN WAR

BEGAN IN

1688, FRANCE

UNLEASHED A

PLAGUE OF

STATE-SANCTIONED

PIRATES UPON

THE ENGLISH

CHANNEL. No

merchant

vessel along

Europe’s

northern

shores was

safe from

these French

privateers

or

“corsairs”.

To be sure,

it was

dangerous

business

being a

corsair but

that did not

discourage a

horde of

French youth

from taking

to the

seas.

When René

Duguay-Trouin

left his

home port of

Saint-Malo

in 1689

aboard an

18-gun

corsair

frigate, the

Trinity,

the

sixteen-year-old

had little

knowledge of

the life he

had embarked

upon. Sea

sickness,

storms, and

shipwreck

welcomed the

young sailor

to the sea.

Then came

battle.

Cruising the

Channel, the

Trinity

crossed

paths with a

Dutch ship

of equal

strength.

The two

vessels

immediately

closed upon

each other

and boarding

parties were

made ready.

Armed with

swords,

daggers,

blunderbusses

and pistols,

the crew of

corsairs

prepared for

their chance

to jump onto

the Dutch

ship.

Initially

enthusiastic,

Duguay-Trouin

turned

cautious

when he

witnessed

his

boatswain

misjudge the

distance,

fall, and

was crushed

between the

colliding

vessels. So

violent was

the

boatswain’s

death, that

Duguay-Trouin’s

clothing was

splattered

with the

poor

sailor’s

brains:

“This object

stopped me

all the more

as I

reflected

that, not

having sea

legs like

him, it was

morally

impossible

for me to

avoid such a

dreadful

kind of

death.” Yet

the young

sailor with

sword in

hand boarded

and received

boarders

while part

of his ship

was ablaze.

Hand to hand

fighting at

the Naval

Battle of La

Hogue, 1692

(Benjamin

West)

When

sixteen-year-old

Duguay-Trouin

returned

victorious

to his home

of

Saint-Malo,

his

experience

did not

dissuade him

from a

pirate’s

life: “This

campaign

which had

made me

consider all

the horrors

of the

shipwreck,

and those of

a bloody

collision

did not put

me off.”

This was the

French

privateer's

hardiness

and

fearlessness

that the

English and

Dutch had to

contend

with.

Hundreds of

ships fell

prey to the

corsairs and

were towed

triumphantly

into the

protected

harbour of

Saint-Malo.

The port’s

taverns and

brothels

became rich

from the

ill-gotten

gains of

their

privateer

cliental.

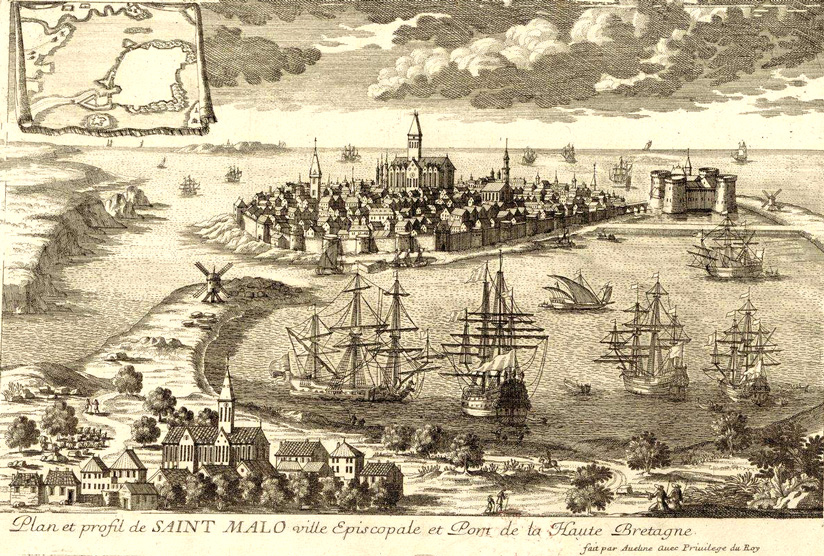

Nestled

behind its

tall walls

and the

newly-improved

harbour

island

forts,

Saint-Malo

was ideally

situated for

corsairs to

pounce on

any vessel

entering the

English

Channel from

the

Atlantic, or

skip across

to the Irish

Sea to reek

havoc on

commerce

there.

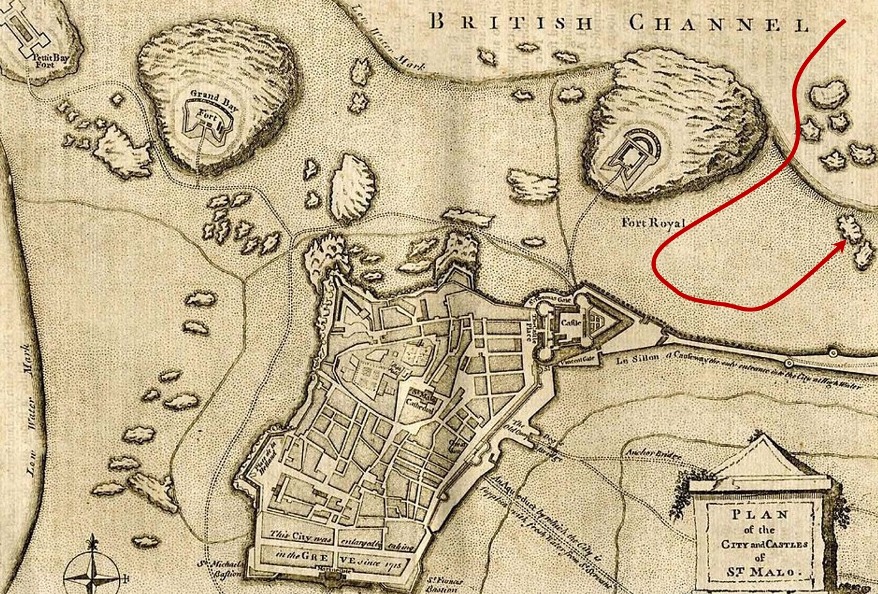

Plan and

profile of

Saint Malo.

(published

1700)

England’s

merchants

clamoured

for action

against the

“nest of

wasps” at

Saint-Malo.

Far from

ruling the

waves,

England

lacked the

strength to

contend with

the corsair

threat on

the high

seas or in

the waters

close to

home.

Looking for

a solution,

a 17th

century

“nuclear

option” was

concocted.

Like the

Manhattan

project of

WW2, the

project was

cloaked in

secrecy.

At the wharf

of the Tower

of London a

strange

vessel was

docked.

Black sails

were mounted

on its

masts.

Hundreds of

barrels were

carefully

rolled out

on board.

Wagons

filled with

explosive

materiel and

projectiles

circled from

the tower to

the dark,

port-less

ship. The

English were

building a

floating

bomb that

the world

had never

seen

before. Its

sole purpose

was the

complete

annihilation

of

Saint-Malo.

It was a

Hellburner.

It was an

Infernal

Machine.

Naval

Ordnance

Engineer

Thomas

Phillips in

1693 just

prior to

setting sail

for Saint

Malo

(National

Maritime

Museum)

Its inventor

was a French

Huguenot by

the name

Fournier who

had fled to

England from

religious

persecution

in his home

country.

Fournier’s

Infernal

Machine was

not a

creature of

half-measures.

Making

Fournier’s

plan come to

life was

navy

ordinance

engineer

Thomas

Phillips;

and it would

be Phillips

who would

light the

fuse. The

300-ton

galleon was

packed with

destructive

material to

cause a hell

of

projectiles

to rain down

upon the

French.

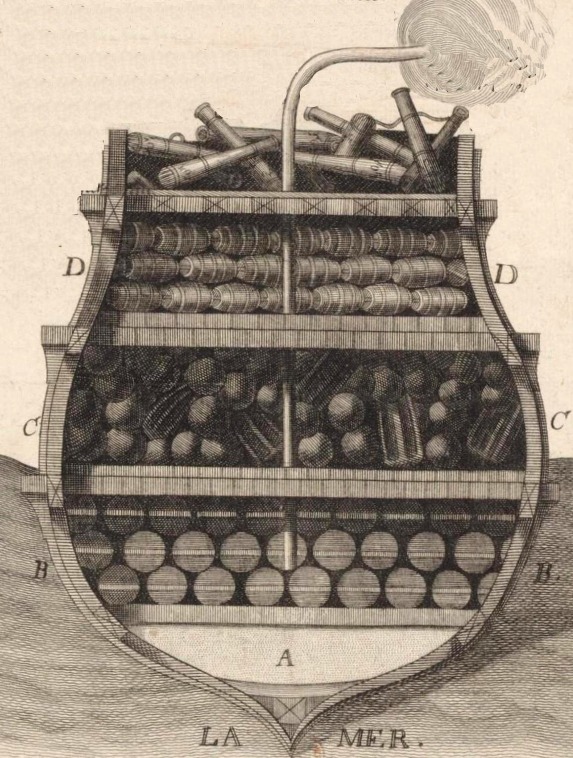

The Infernal

Machine

(published

1697). Part

of the ship

was studied

by French

engineers

who made

this

drawing.

At the base

of its haul

was a layer

of sand to

soak up any

moisture and

add ballast.

(A on the

above

illustration)

The sand was

covered with

masonry on

which over a

100 barrels

of gunpowder

were laid.(B)

Separated by

two feet of

masonry was

the next

level

containing

six hundred

tarred-linen

"carcasses

and chests

filled with

grenades,

cannon-balls,

iron chains,

loaded

firearms,

large pieces

of metal

wrapped up

in

tarpaulins,

and other

destructive

missiles.”(C)

When the

ship

exploded the

carcasses

would be

launched

into the air

and land on

houses or

ships

catching

them on

fire. The

grenades and

loaded

firearms

would then

explode or

fire off

randomly

discouraging

the French

from

fighting the

fire caused

by the

carcass

(learn more

about

carcasses

here).

Fifty

barrels

filled with

projectiles

and

fireworks-like

missiles

composed the

next

level.(D)

On the deck

was a pile

of loaded

cannon

barrels,

packed with

gun powder

and ball to

explode. As

an

additional

measure if

the cannon

barrels fell

into enemy

hands

intact, they

were made

useless by

knocking off

their

trunnions.

Without

trunnions,

the barrels

could not be

mounted on a

cannon

carriage.

Along with

the cannons

were mortars

loaded with

fused

exploding

shells.

To make the

ship explode

several

holes were

drilled from

the top deck

down to the

powder

barrels

below and

quick match

was laid.

There were

a number of

fuses, not

just one as

the

illustration

above

suggests.

Crew member

had to light

the matches,

scurry off

the ship to

a waiting

boat and

then row

like mad.

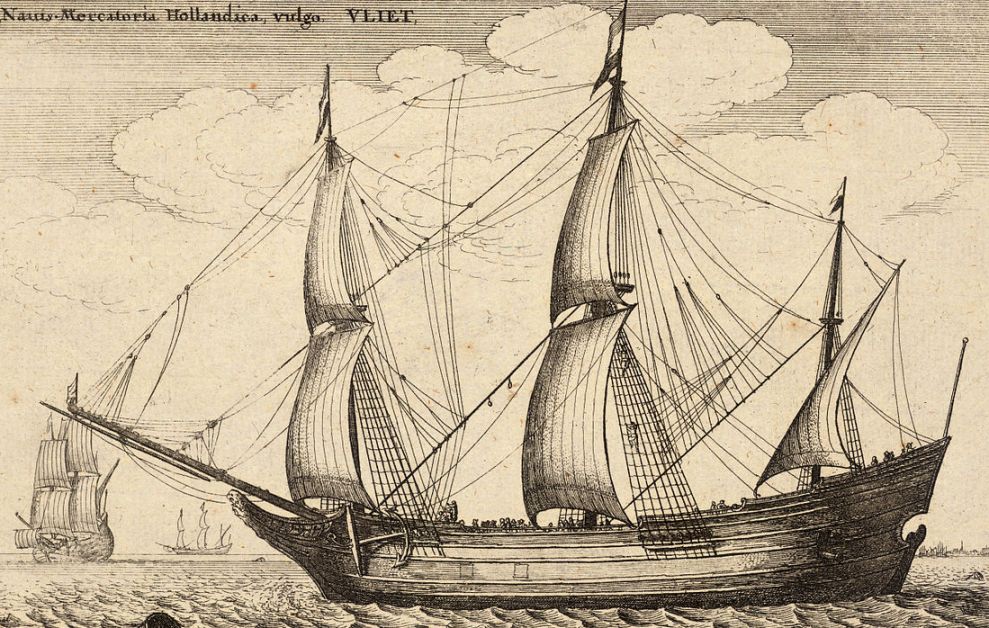

Dutch Flyte

Ship

(published

1677).

Similar to

the earlier

galleon in

cargo space

but faster

and with a

shallower

draft. The

Infernal

looked

like this

ship.

The

Infernal

had a

shallow

draft to

allow it to

pass through

shallow

waters and

get close to

Saint-Malo’s

fortification

where the

garrison

powder

magazine was

located.

That way

when the

infernal

machine

blew, the

French

powder

magazine

would feed

the

explosion

and bring

hell to the

entire nest

of pirates.

Captain John

Benbow, 1701

by Godfrey

Kneeler

(National

Maritime

Museum)

Benbow was

one of the

most

determined

officers in

the Royal

Navy in the

war.

In his last

battle he

led his crew

even after

being

wounded in

the leg with

chain-shot.

On November

13th, 1693 a

fleet of

twelve

warships,

twelve

brigantines,

four bomb

vessels

armed with

mortars for

shelling,

and the

Infernal set

sail for

Saint-Malo

under the

command of

the gallant

Captain John

Benbow.

Benbow had

oversaw the

infernal

ship project

and was keen

to see the

results of

the

enterprise.

However

Benbow’s

objective

was destroy

Saint-Malo

and the

Infernal

was only

weapon in

his

arsenal.

On the

afternoon of

November

16th, the

majority of

the fleet

drove

towards

Saint-Malo

on a strong

wind from

the north

riding a

great swell

and strong

tide. For

hours the

Royal Navy

crews

struggled in

the swirling

and

treacherous

waters to

position

their

vessels to

bombard the

city. It was

not until 10

o’clock at

night that

they were

able to

moor. From

that time

until 4

o’clock in

the morning

the fleet

bombarded

Saint-Malo,

lobbing

mortar

shells and

flaming

metal-banded

carcasses

over the

city's

walls.

With the

tide going

out, the

fleet had to

warp out of

the bay or

risk being

grounded on

the sand

bars that

surrounded

Saint-Malo.

The pattern

of

bombardment

continued

for the next

two days,

with the

bomb vessels

firing

hundreds of

bombs and

carcasses

into the

city.

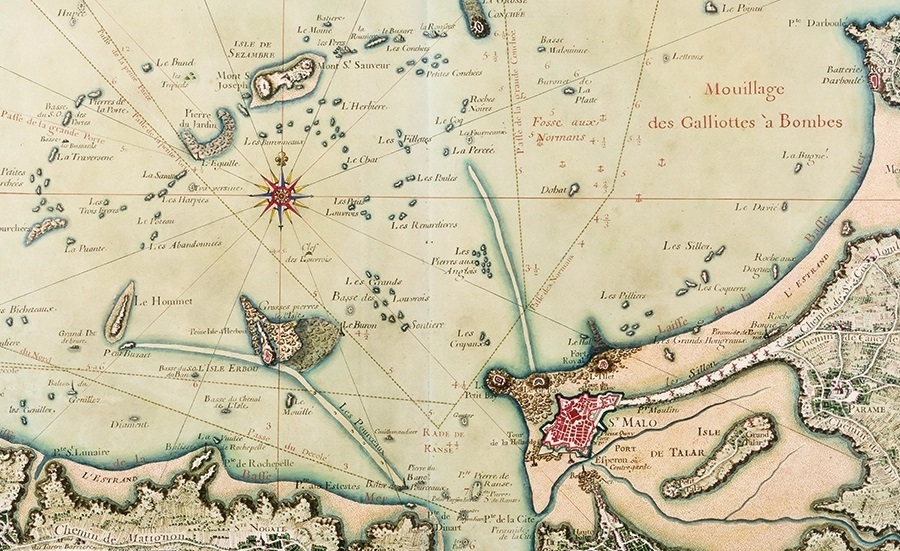

The

navigation

around Saint

Malo. The

tan areas

are the sand

bars that

appear when

the tide is

out. The

English

needed to

come in with

the tide to

get close

enough to

bomb

Saint-Malo.

With the

arsenals of

the bomb

vessels

almost

expended,

the

Infernal

was called

forward on

the evening

of November

19th

. As a

diversion,

the fleet

dispatched a

landing

party to

overwhelm a

small

garrison and

burn a

convent on a

nearby

island.

Masked by

this flaming

spectacle on

the horizon,

the

Infernal,

with its

black sails

unfurled,

moved in.

On board was

Engineer

Phillips and

a skeleton

crew to

navigate the

ship through

the many

rocks and

shoals

littering

the approach

to the walls

of

Saint-Malo’s

old

stone-towered

citadel.

Under the

cover of

night the

Infernal

sailed

closer and

closer to

its

destination.

Just when

the ship was

almost in

place the

wind

suddenly

veered,

driving the

Infernal

out and onto

a rock.

Several

attempts

were made to

clear the

vessel from

the rock but

all were in

vain.

Phillips

soon

discovered

the haul had

been

punctured

and water

was leaking

into the

gunpowder

hold. With

little

options,

Phillips lit

the fuses

and he and

his crew

made their

escape.

Path of the

Infernal

Machine

showing the

impact of

the change

in wind.

French

historians

believe it

was much

further from

the Saint

Malo and

became

ground on

what is

called les

Pierres aux

Anglais (see

other map).

This

distance

seems too

far to hurl

the ship's

heavy

capstan into

the city.

Then hell

opened up.

The ship

went up in a

deafening

explosion

that shook

Saint-Malo

like an

earthquake.

Roofs were

blown off

houses, the

protecting

sea wall of

the Citadel

collapsed,

the wind

vanes of

nearby

windmills

were ripped

off, and the

concussion

“broke all

the glass,

china, and

earthenware

for three

leagues

round.”

Projectiles

rained down

all about.

Hundreds of

bombs and

grenades

continually

exploded

sending the

French

population

into a

panic.

Flaming

carcasses

fell from

the sky in

every

direction.

Miraculously

part of the

ship

survived due

probably to

wet

gunpowder in

that part of

the haul.

The Infernal

Machine

explodes

(published

1694).

Island

buildings

burn in the

foreground.

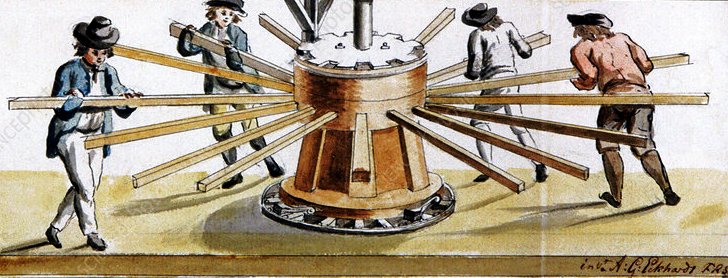

Ship's

Capstan

worked by

sailors

(published

1700). The

two-thousand-pound

capstan of

the

Infernal

landed in

the Saint

Malo's

square

destroying a

house.

While it was

an

incredible

spectacle

causing

substantial

property

damage and

striking

terror deep

into the

hearts of

the people

of Saint

Malo, the

infernal

machine had

failed. Saint

Malo was

damaged but

was still

intact.

Possibly

broken-hearted

Thomas

Phillips

would fall

ill and die

three days

later.

The only

death noted

by the

French was a

cat. “Rue

du Chat-qui-Danse”

or street of

the Dancing

Cat in

Saint-Malo

was named

after the

unfortunate

feline as a

mockery of

the English

attempt to

destroy

their

city. But

behind the

bravado was

a deep fear

of this new

weapon.

French ports

scrambled

for a

solution to

protect

themselves

from

destruction.

Captain

Benbow was

not finished

with the

infernal

machines and

two more

were ready

and a new

attack was

made, this

time on

Dieppe.

However,

French had

adapted by

blocking the

harbour with

sunken

vessels and

the infernal

machines had

little

effect.

When the war

ended in

1697,

infernal

machines

were

abandoned.

It would be

over a

hundred

years before

an infernal

machine

would be

used to try

and blow up

another

pirate nest.

POSTSCRIPT

Debris rains

down from

the Halifax

explosion.

On December

6th 1917, a

French cargo

ship filled

with high

explosives

collided

with another

vessel in

the harbour

of Halifax,

Nova

Scotia. The

dangerous

cargo

ignited and

the ship

exploded.

All

structures

in the city

for half a

mile were

levelled,

killing 2000

people and

wounding

9000

others. The

concussion

wave snapped

trees and a

resulting

tsunami wave

beached

ships and

washed away

a Mi’kmaq

village.

Parts of the

French ship

were found

miles away

from the

explosion.

Twenty

thousand

people were

left

homeless

when a

winter

blizzard hit

the day

after.

This

accidental

infernal

machine

shows the

damage Saint

Malo could

have faced

if the wind

had not

suddenly

changed on

November

19th, 1693.

The cloud

from the

Halifax

explosion