|

Why Palm Out?

A History of the British Army Hand Salute

French and Indian War - American Revolution - Wellington's Army - Victorian Wars

Officer of the British Corp of Riflemen saluting. The image is contrary to the unit's 1801 Standing Order to salute "in a horizontal but circular position; the points of the forefinger and thumb meeting the edge of the helmet". (image published 1801)

ARMY PRACTICES THAT HAVE STOOD THE TEST OF TIME ARE OFTEN FOUNDED ORIGINALLY AS A PRACTICAL SOLUTION TO A PROBLEM. The hand salute of the American and British armies is no different. How officers and soldiers greeted each other, when not carrying a firearm or a drawn sword, is uncovered here. It's origins may surprise you. Before continuing it is important to point out that in the 18th century the term "hat" was a headdress with a brim like a tricorn, or cocked hat. On the other hand, "caps" did not have brims like mitres, bearskins, shakos, helmets and so on. However "caps" could have peaks.

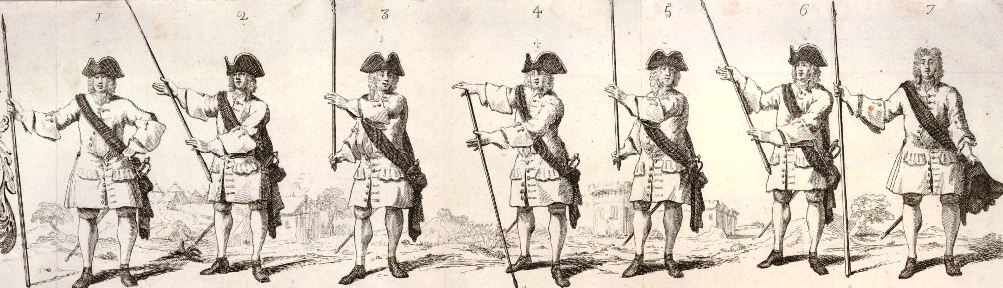

For the first half of the 18th century, when officers encountered another officers, a socially common greeting was used. They were gentlemen from society's higher classes and military salutes were left to the parade square when they were armed with their pikes.

British Officer Saluting with his Pike at a General review. (published 1728) Removal of the hat was essentially the same to 1786.

In 1740, the "French salute", or greeting another by kissing them on the cheek, started to become fashionable in London. On one occasion at a coffee house an English army captain crossed paths with his cousin who was a Royal Navy lieutenant. The captain "met him with a la mode de Paris, with open Arms, and was going to salute his right cheek" but the Navy lieutenant grabbed his cousin in a "manly" hug that almost knocked the wind out of him. The "French salute" quickly became controversial, being called un-English. Encouraged instead was the "old English" way of "pulling off a Hat, or... a hearty Shake of the Hand." One Englishman's dislike of the French greeting was put to verse in 1741:

That you salute me on one cheek along,

I thank you; but would me, was that not done:

For what I wou'd the greatest favour call,

Is, that you's never kiss me, Sir, at all.

For the British, removing your hat became the socially acceptable salutation for the rest of the 18th century. It also had been established as early as 1727 that when passing a superior officer, a junior officer was to show his subordination by removing his hat. However bowing to the superior officer was discontinued. This way of greeting superiors remained the case for the rest of the century.

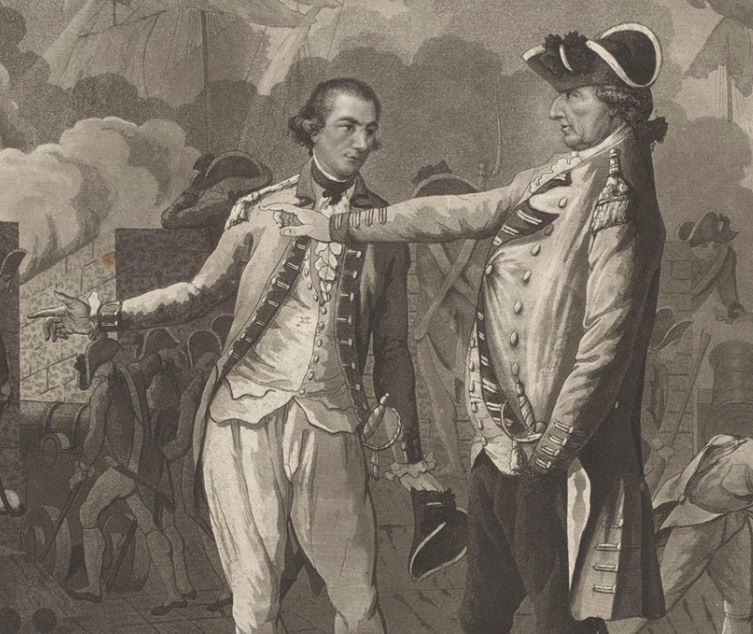

Subordinate officer receiving orders from General Elliot at the siege of Gibraltar (published 1782)

This was similar to when a common soldier, without arms, met an officer. Until the 1740s it was common practice for the soldier to remove his hat with both hands and bow to the officer with eyes often downcast or averted. Concerned with this practice damaging the soldier's hat, the 2nd Regiment of Foot Guards (Coldstream's) in September 1745 ordered them "not to pull off their hats when they pass an officer, or to speak to them, but only to clap up their hands to their hats and bow as they pass by." However there is no evidence this practice was widespread in the army. That said the problem of protecting the white lace and shape of the soldier's hat from damage remained.

The Royal Regiment of Foot (Royal Scots), (published 1742)

As a whole, while the Army's common soldiers continued to remove their hats as a salutation to their officers, some regimental commanders tired of the slovenly look of their solder's headdress. At the end of Seven Years War (French and Indian War in North America), Major Dalrymple of the Royal Scots in 1762 ordered:

"As nothing disfigures the hats or dirties the lace more than taking off the hats, the men for the future are only to raise the backs of their hands to them with a brisk motion when they pass an officer. when at any time they have occasion to take off their hats entirely it must be with great care!!"

Unknown from this order is whether it refers to one hand or both, like the Guards order of 1745. This is the first reference to the palms pointing outward, the purpose of which to protect the hat's white lace from any filth on the soldier's hands. A sketch in 1759 by Brig. General Goerge Townshend during the siege of Quebec of a soldier digging a latrine suggests a wider use of this salute amongst the army. One hand is being used, though the other has a shovel in it and the soldier could be a grenadier.

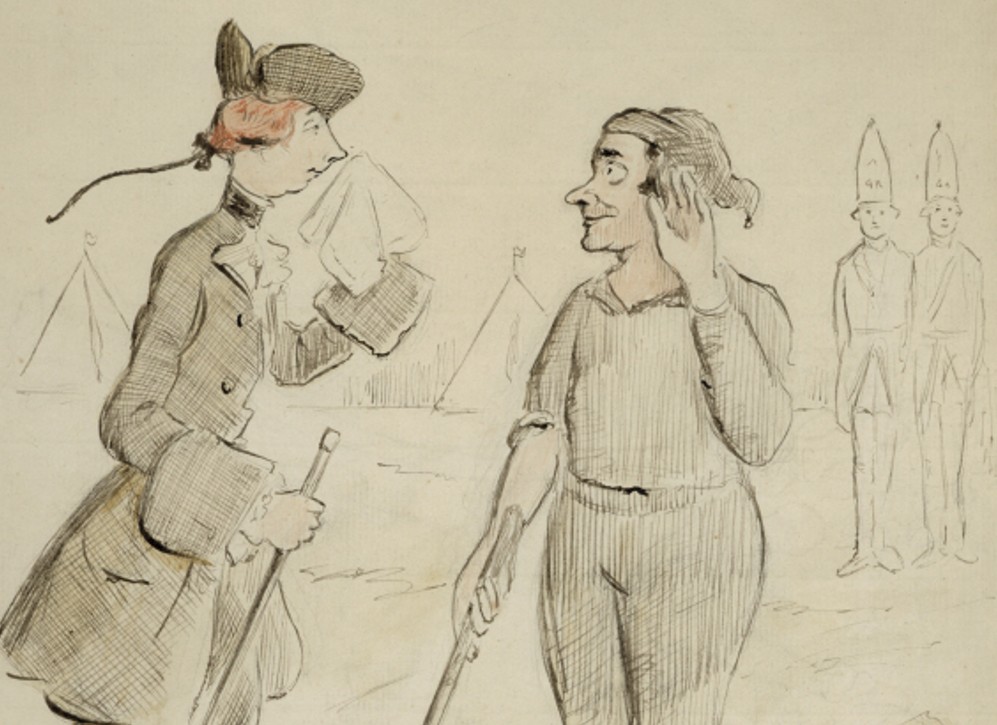

| At the beginning of the French and Indian War soldiers removed their hats with two hands when paying their respects to an officer. |

Highland soldier servant removing his bonnet while approaching his lieutenant in Flanders, 1743.

He is using one hand because his other is carrying a canteen.

A tug-a-war between whether or not to remove the hat continued in the Army. In 1768 Captain Bennett Cuthbertson of the 5th Regiment of Foot suggested a solution with the one-hand removal of the hat:

"Soldiers... may have an opportunity of showing their respect, by taking off their their hats with the left hand, and letting them fall in an easy graceful manner down the thigh, with the crown inwards... looking full at the Officer they intend to compliment with a manly confidence and walking by him very slow: this method, when executed properly, will have a much more striking effect, than only putting the hand to the hat, and will be found not to injure the cock of it one bit more, notwithstanding that objection is made against it by several military persons."

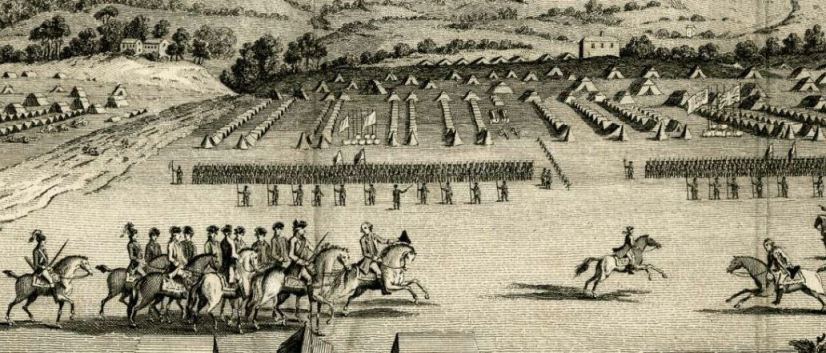

This implies that prior to 1768, most soldiers removed their hats with two hands when paying their respects to an officer. At the massive Coxheath military camp in 1778, removing hats seemed to have won out: "All soldiers in this camp when they pass or are passed by an officer will pull off their hats to him, which they will do in two motions with life." The order reference to "with life" suggests a brisker pace than that recommended by Cuthbertson.

Coxheath Military Camp (published c1778). Note the officer riding with his hat off addressing his superior.

Norfolk Militia officer saluting with fusil and hat. (published 1768)

The battle seemed decided, but other regiments challenged the removing of the hat. For example, the 62nd Regiment in 1781 ordered each soldier to bring his right hand up "smart to the side of his Hat." Using the right ensured the hand did not damage the cockade. It is uncertain whether the gesture was a touch of the hat to mimic removing it (like the French Army at the time) or was a palm-out salute.

| The new drill of the British Grenadiers in 1727 is the true origin of the somewhat unnatural palm-out hand salute. |

Running parallel with the debate around the removal of the soldier's hat, was the introduction of a salute for soldiers wearing grenadier, drummer, or light infantry caps. Unlike the hat, the adoption of a proper hand salute for caps seemed universal. Cuthbertson noted that when an officer passed by, soldiers wearing caps were brought up "the back of the hand" that was furthest from the officer to the front of the cap "with graceful motion." The salute was held "as long as they would remain with their hats off."

A Grenadier Sergeant of the 25th Regiment of Foot saluting. The use of the left hand may be because he is delivering (reading) his report in his right hand (National Army Museum).

This salute was first used by the British Grenadiers and can be traced back to 1727. It is the true origin of the somewhat unnatural palm-out hand salute. Prior to beginning their exercise of throwing the grenade, the grenadiers performed a special salute that had

"a very good effect, both on the spectators and performers, by preparing the latter to go through their exercise with life, vigour, and exactness, in which the principal beauty of exercise consists. The motions are as follows: First, the Grenadiers bring up their right hands briskly to the front of their caps. then tell 1,2 [pause for the count of two] and bring them down with a slap on their pouches, with all the life imaginable."

During this exercise, the pouch was worn to the front of the body and the hand with palm outward descended straight down to hit it. This preparatory salute remained a part of the drill to about 1760, when grenades were no longer being widely used by the grenadiers.

Grenadier of the 1st Foot Guards in 1735. The cap worn should be blue. Note the position of the grenade pouch. This grenade exercise was popularized when an illustrated pamphlet was published in 1744.

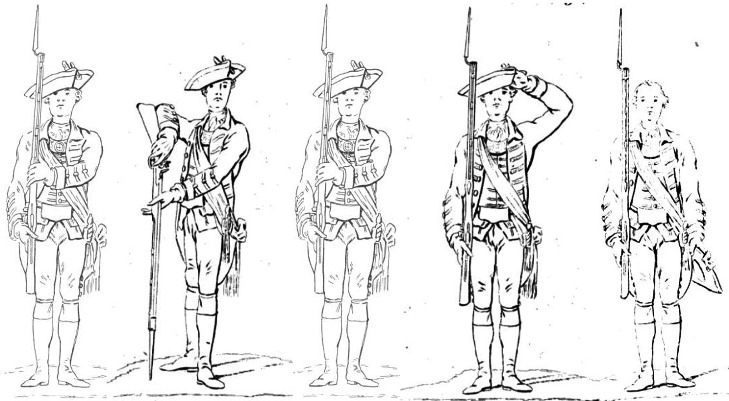

In 1778, the Nottingham Regiment of Marksmen explained the palm-out cap salute by using positions of drill as reference: "with a brisk motion bring the hand into the same position as for returning the Rammer in Exercise (with the elbow well raised) taking care only, that it may be so high as not to hide their eyes, and they look full at the officer." For officers wearing caps, they also adopted the hand salute. The below illustrations show Light infantry officers using the palm-out hand salute during General review, as ordered in 1786. Grenadier officers did the same.

1786 standing and marching salute with fusil (published in 1795) It appears the hand salute was maintained for grenadier and light company officers throughout the Napoleonic Wars even when they were only armed with swords.

By the 1790s the officer's hat had evolved into a bicorn providing a flat front. Saluting with the sword and the palm out hand was briefly adopted in the late 1790s, but soon disappeared with a change in headdress to the fore-and-aft chapeau bras in the early 1800s. A palm-out hand salute was not practical with this hat. Meanwhile in 1800, soldiers of infantry regiments all abandoned the hat and adopted the stove-pipe shaped cap called a shako. As a result all infantry soldiers adopted the salute of the grenadiers and light corps.

Wearing a headdress different from the common soldier made hat-wearing infantry officers targets of French sharpshooters. As a result, in 1812 all infantry officers adopted caps and as a result "all officers dismounted, wearing caps, are to salute in the same manner as practiced by officers of " the grenadiers and light infantry (the flank companies). During this period the hand salute became more refined by regiments. For example the 33rd Regiment of Foot ordered the soldier to "raise the hand gracefully, not with a jerk, to the cap, the elbow raised square with the shoulder, the hand flat, the forefinger and thumb touching the cap in front." In 1813 another regiment, the 85th Light Infantry, added a little more flourish to the hand salute:

"the hand with the back part upwards is carried out upon a line with the should to the full extent of the arm, then brought slowly round with an extended arm, until the hand touches the cap, when by a smart turn of the wrist, the inside of the hand is turned outwards with the back of the fingers touching the cap."

Sadly for the 85th, the "smart turn of the wrist" palm-out British hand salute ended the following year.

| ...the "smart turn of the wrist" palm-out British hand salute officially ended in 1814...at the Battle of Waterloo the British Army was using the horizontal hand salute. |

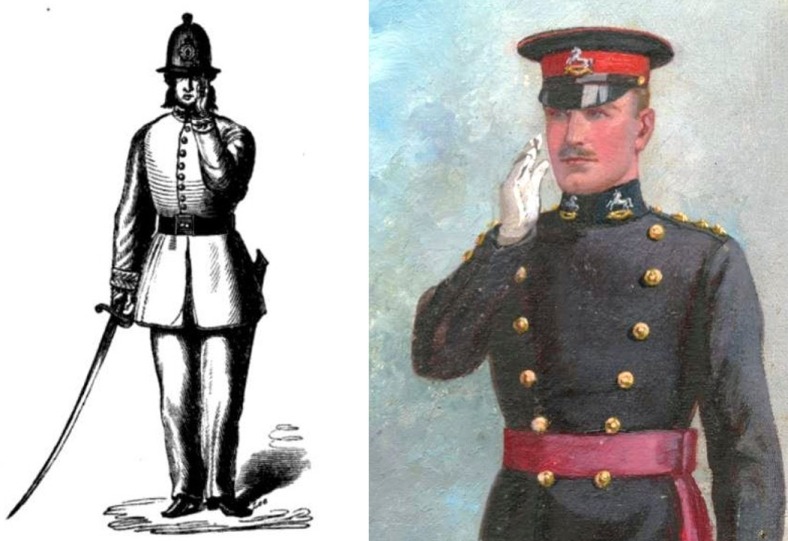

On April 18, 1814, Horse Guards ordered all officers, when swords not drawn, "to salute, by bringing up the right hand to the forehead, horizontally, on a line with the eyebrows." This new horizontal salute was immediately ordered to be "in the same manner" for the other ranks. Why the sudden change? Evidence points to the move as not sudden at all. For example in 1812, when all officers were ordered to salute like the grenadier and light companies, the 7th Regiment of Foot (the Royal Fusiliers) interpreted the order during parades salutes as: "with arms the officer's salute, according to the flankers, viz. in dropping the sword the left hand to be brought gracefully to the cap horizontally, with the palm down." This order suggests that flank company officers continued to salute with their hand when performing a sword salute. During the Napoleonic Wars, the battalion officers only saluted with their sword on parade, but it appears grenadier and light infantry officers preserved their hand salute with arms. Another point is, at least with the Royal Fusiliers, the flank company officers were performing a horizontal salute prior to the 1812 order. As early as 1801 the Rifle Corps saluted "in a horizontal but circular position; the points of the forefinger and thumb meeting the edge of the helmet." Touching the forefinger and thumb points can only be done in a palm-down fashion, though the Rifles appear to be curving the hand.

Drum Major of the Staffordshire Militia in 1804 salutes palm down but thumb extended to touch his brim. This illustrates the problem with the hand saluting to a brimmed hat. The Drum Major uses his thumb to judge the distance to the hat so he does not knock his hat off. This can only be done by saluting palm-down. The salute is an anomaly but necessary because there was no salute with the mace at the time. (National Army Museum)

In 1820, orders of the 26th Regiment of Foot offered a little more detail on the new salute: "the hand is to be placed gracefully along the peak of the cap in a horizontal position, the fingers fully extended and the hand flat." If there was any doubt on the birth of the horizontal salute in the British Army, the 1851 Standing Orders of the 53rd Foot spelled out: "The mode of saluting is laid down in the General Orders, &c. of the Army." All the published Army Regulations (1822, 1837, 1844 and 1860 editions) repeated word-for-word the 1814 order. It was the only reference to the hand salute in the General orders. Therefore at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 the British Army were using the horizontal hand salute.

Left to right: 6th Foot in 1839; 86th Foot in 1842; and 12th Foot in 1848. All performing the horizontal hand salute. The position of the visor impacted the location of the hand. With the bell-topped shako the hand was on the peak to align it with the eyebrows, while with the 1844 Albert Shako the hand simply touched the edge of the peak.

For the next forty-five years the horizontal hand salute was the norm for the British Infantry. Below is a soldier photographed in the Crimean War performing the palm down, eyebrow level hand salute.

47th Regiment of Foot private performing the horizontal hand salute, 1855 (photograph by Roger Fenton)

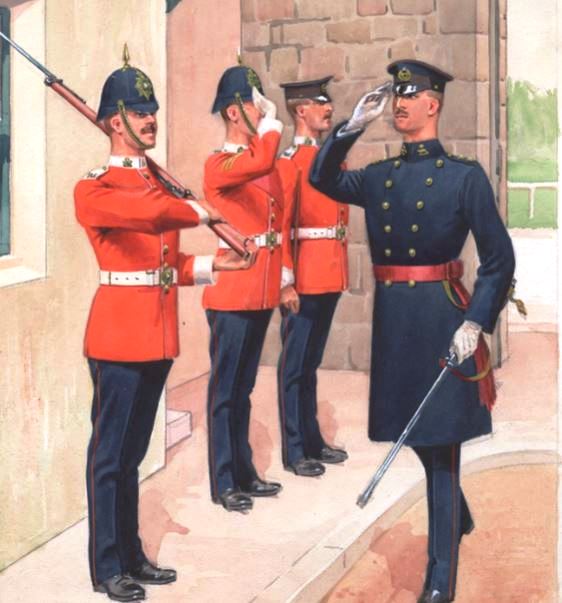

As an almost nostalgic throw back to the 18th century, the army decided in 1870 to have a different salute for the other ranks. The palm-out hand salute was back. This was clearly influenced by the adoption of the palm out salute by other powers such as France and the United States. The first motion of the salute was to "bring the right hand smartly, but with a circular motion, to the head, palm to the front, point of the forefinger one inch above the right eye, thumb close to the forefinger; elbow in line, and nearly square, with the shoulder; at the same time, slightly turn the head to the left." The last motion of the salute is illustrated below:

2nd Motion of the 1870 Hand Salute for the Army. The Royal Artillery adopted it in 1875.

York and Lancaster Regiment c1899 (published 1900). This shows the two types of salute.

A vertical salute for the officers emerged in 1859. This salute allowed company officers in closed ranks to perform a sword salute without elbowing the soldier beside them. It was performed by "raising the left arm as high as the shoulder, and bringing the hand, knuckles uppermost and fingers extended to the peak of the shako." While only intended for the sword salute, this salute was adopted by some regiments to replace the horizontal salute.

Left: A British Constable performs the vertical salute (published 1868). Right: King's Regiment officer saluting c1899 (published 1900)

British Officers continued to salute differently from the other ranks for forty years. In 1899, the Queen's Regulations put an end to this duality by ordering all officers to "salute with the right hand, in the manner prescribed for soldiers."

Invented in 1727 as a precursor to a pouch slap, the palm-out salute was abandoned in 1814 only to be resurrected in 1870 and then made universal in the British Army in 1899. It's initial adoption was heavily influenced by the variety of military headdress at the time. While the British Army hand salute has not changed since 1899, the rocky road it travelled had, until now, been forgotten.

----------------

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

----- A Manual of Drill and Sword Exercise Prepared for the Use of the County and District Constables. 4th Edition. London, 1868

----- "Regulations for the Rifle Corps, 1801, Formed at Blatchinton Barracks under the Command of Colonel Manningham", Rifle Brigade Chronicle. 1897.

----- Standing Orders and Regulations for the 85th Light Infantry. London, 1813.

----- "Standing Orders of the 33rd Regiment [August 1811]" The Iron Duke. Nos. 43, 44, 45, & 46. 1939-1940.

----- Standing Orders of the 7th (or Royal Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot. London, 1812.

----- The Granadiers Exercise of the Granado in his Majesty's First Regiment of Foot Guards. London, 1744.

----- The London Magazine: and Monthly Chronologer. London, 1741

----- The Royal Military Panorama or Officer's Companion. Volume 4. London, 1814.

Adjutant General's Office, Field Exercise and Evolutions of Infantry. London (1824, 1859, 1870 and 1877 Editions)

Adjutant General's Office, Infantry Sword Exercise. London (1817, 1845, and 1854 Editions)

Adjutant General's Office, General Regulations and Orders for His Majesty's Forces, London (1786, 1805, 1812, and 1819 editions).

Humphrey Bland [Lieut. General], A Treatise of Military Discipline. London. (1727, 1743, 1746, and 1759 Editions)

Richard Cannon, Historical Record of the Sixth or Royal First Warwickshre Regiment of Foot. London, 1838.

Richard Cannon, Historical Record of the Twelfth, or the East Suffolk Regiment of Foot. London, 1848.

Richard Cannon, Historical Record of the Eighty-sixth, or the Royal County Down Regiment of Foot. London, 1842.

Bennet Cuthbertson [Captain], A System for the Compleat Interior Management and Economy of a Battalion of Infantry. London, 1768.

Bennet Cuthbertson, Cuthbertson's System for the Complete Interior Management and Economy of a Battalion of Infantry. Bristol, 1776.

Horse Guards, The King's Regulations and Orders for the Army. London. (1822 and 1837 Editions)

Mansfield [Lt. Col.], Revised Standing Orders of the Fifty-Third Regiment of Foot. Calcutta, 1851.

Edward Mathew [Major General] Regimental Standing Orders for the Sixty-Second Regiment of Foot. 1781.

Richard Philips, The British Military Library. Vol. 2. London, 1801

Timothy Pickering, An Easy Plan of Discipline for a Militia. Salem, 1775.

George Sutton, Orders and Instructions to the Nottinghamshire Regiment of Marksmen. Hull, 1778.

War Office, The Queen's Regulations and Orders for the Army. London. (1844, 1860, 1868, 1889 and 1899 Editions)

William Windham, A Plan of Discipline for the Use of The Norfolk Militia. London, 1768.

Library and Archives Canada, Record Group 8, C Series, vol. 1169 p. 21 General Order, Horse Guards, July 10, 1812.

Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research

J.H.L. "Saluting" Vol. 2, No. 9 (July, 1923) [referencing Royal Scot's 1762 Standing Orders originally published in Regimental Records of the Royal Scots (Dublin, 1915)]

G.O. Rickword, "Saluting" Vol. 20 No. 80 (Winter, 1941) [referencing Coldstream Guards September 1745 order originally published in Origins and Services of the Coldstream Guards, 1833.]

Charles Herbert, "Coxheath Camp, 1778-1779" Vol. 45, No. 183 (Autumn, 1967).

René Chartrand, "Saluting" Vol. 66, No. 265 (Spring, 1988).

|

Author Robert Henderson enjoys unearthing and telling stories of military valour, heritage, and sacrifice from across the globe. Lest we forget. |

MORE FREE ARTICLES like this one can be found here:

|