This

cannonade was but the prelude of the attack that the enemy were

developing, and I looked upon the moment when they would fling

themselves against one point or another in our entrenchments as so

instant that I would allow no man even to bow his head before the

storm, fearing that the regiment would find itself in disorder when

the time came for us to make the rapid movement that would be

demanded of us. At last the enemy's army began to move to the

assault, and still it was necessary for me to suffer this sacrifice

to avoid a still greater misfortune, though I had five officers and

eighty grenadiers killed on the spot before we had fired a single

shot.

So

steep was the slope in front of us that as soon almost as the

enemy's column began its advance it was lost to view, and it came

into sight again only two hundred paces from our entrenchments. I

noticed that it kept as far as possible from the glacis of the town

and close alongside of the wood, but I could not make out whether a

portion might not also be marching within the latter with the

purpose of attacking that part of our entrenchments facing it, and

the uncertainty caused me to delay any movement. There was nothing

to lead me to suppose that the enemy had such an intimate knowledge

of our defences as to guide them to one point in preference to

another for their attack.

English and

Allied troops constructing Fascines or bundles of brush.

Fascines were carried by the attacking force to use to bridge the

ditches so

as to better climb the Franco-Bavarian parapet defences.

However many were prematurely used to traverse gullies carved by the

previous day's heavy rain. (detail from Victoria &

Albert Museum)

Had I

been able to guess that the column was being led by that scoundrel

of a corporal who had betrayed us, I should not have been in this

dilemma, nor should I have thought it necessary to keep so many

brave men exposed to the perils of the cannonade, but my doubts came

to an end two hours after midday, for I caught sight of the tips of

the Imperial standards, and no longer hesitated. I changed front as

promptly as possible, in order to bring my grenadiers opposite the

part of our position adjoining the wood, towards which I saw that

the enemy was directing his advance.

The

regiment now left a position awkward in the extreme on account of

the cannon, but we soon found ourselves scarcely better off, for

hardly had our men lined the little parapet when the enemy broke

into the charge, and rushed at full speed, shouting at the top of

their voices, to throw themselves into our entrenchments.

The

rapidity of their movements, together with their loud yells, were

truly alarming, and as soon as I heard them I ordered our drums to

beat the "charge" so as to drown them with their noise, lest they

should have a bad effect upon our people. By this means I animated

my grenadiers, and prevented them hearing the shouts of the enemy,

which before now have produced a heedless panic.

|

"quite

impossible to find a more terrible representation of

Hell itself than was shown in the savagery of both sides

on this occasion." |

The

English infantry led this attack with the greatest intrepidity,

right up to our parapet, but there they were opposed with a courage

at least equal to their own. Rage, fury, and desperation were

manifested by both sides, with the more obstinacy as the assailants

and assailed were perhaps the bravest soldiers in the world. The

little parapet which separated the two forces became the scene of

the bloodiest struggle that could be conceived. Thirteen hundred

grenadiers, of whom seven hundred belonged to the Elector's Guards,

and six hundred who were left under my command, bore the brunt of

the enemy's attack at the forefront of the Bavarian infantry.

It

would be impossible to describe in words strong enough the details

of the carnage that took place during this first attack, which

lasted a good hour or more. We were all fighting hand to hand,

hurling them back as they clutched at the parapet ; men were

slaying, or tearing at the muzzles of guns and the bayonets which

pierced their entrails ; crushing under their feet their own wounded

comrades, and even gouging out their opponents' eyes with their

nails, when the grip was so close that neither could make use of

their weapons. I verily believe that it would have been quite

impossible to find a more terrible representation of Hell itself

than was shown in the savagery of both sides on this occasion.

English and

Dutch troops attacking a field entrenchment in 1709

(Battle of Malplaquet - Wiki)

At

last the enemy, after losing more than eight thousand men in this

first onslaught, were obliged to relax their hold, and they fell

back for shelter to the dip of the slope, where we could not harm

them. A sudden calm now reigned amongst us, our people were

recovering their breath, and seemed more determined even than they

were before the conflict. The ground around our parapet was covered

with dead and dying, in heaps almost as high as our fascines, but

our whole attention was fixed on the enemy and his movements ; we

noticed that the tops of his standards still showed at about the

same place as that from which they had made their charge in the

first instance, leaving little doubt but that they were reforming

before returning to the assault. As soon as possible we set

vigorously to work to render their approach more difficult for them

than before, and by means of an increasing fire swept their line of

advance with a torrent of bullets, accompanied by numberless

grenades, of which we had several wagon loads in rear of our

position. These, owing to the slope of the ground, fell right

amongst the enemy's ranks, causing them great annoyance and

doubtless added not a little to their hesitation in advancing the

second time to the attack. They were so disheartened by the first

attempt that their generals had the greatest difficulty in bringing

them forward again, and indeed would never have succeeded in this,

though they tried every other means, had they not dismounted and set

an example by placing themselves at the head of the column, and

leading them on foot.

The "numberless

grenades" the French and Bavarians threw at the attackers were of

this configuration. They were hollow

iron balls about 3 1/2

inches (8 cm) in diamater and filled with gunpowder. A wooden fuse

and match cord soaked

in potassium nitrate served as its ignition

device. A number of 18th century grenades were found on the wreck of

the

French 32-gun frigate Machault. To the right,

a Bavarian Grenadier is shown tossing one of these fragment

grenades.

(painting: Anton Hoffmann)

Their

devotion cost them dear, for General Stirum and many other generals

and officers were killed. They once more, then, advanced to the

assault, but with nothing like the success of their first effort,

for not only did they lack energy in their attack, but after being

vigorously repulsed, were pursued by us at the point of the bayonet

for more than eighty paces beyond our entrenchments, which we

finally re-entered unmolested.

After

this second attempt many efforts were made by their generals, but

they were never able to bring their men to the assault a third time.

They remained halted half-way in a state of uncertainty, seeking an

opportunity of extricating themselves and improving their position.

They

had all along feared the effect of the fire from the covered-way of

Donauwort, and this was why they had narrowed their attack along the

edge of the wood ; having failed, therefore, to penetrate our

particular angle of the entrenchments, they sent off a lieutenant

and twenty men in the direction of the town to reconnoitre it

closely. This officer, who fully believed he had received his

sentence of death, was agreeably surprised to find the glacis

deserted, and his party only received a few shots from the loopholes

in the old walls of the town.

The

town commandant, upon whom Maréchal d'Arcko had relied so much,

instead of lining his covered-way with his best troops, had

withdrawn them all into the main works ; he seems to have considered

that the best way of ensuring the safety of the place was to shut up

his troops and lock the gates, and the result was our ruin. It is

quite certain that if he had occupied the covered-way, as was

naturally to be expected, the enemy would never have been able to

get into our entrenchments, for they would have found it impossible

to do so under the flank fire from the glacis, against which they

could have in no wise protected themselves. I am of opinion even,

that had they cared to run this risk we should have had notice of

their line of advance from the resistance offered by the garrison,

in time to have afforded support in that quarter by filing to our

left along our entrenchments. As it was, we were not in a position

to know anything of this, owing to the formation of the ground which

hid their movements from us ; and at the same time it seemed clear,

owing to the resistance maintained against them at every point and

the great loss they had suffered in their repulse, that their chance

of success in a third assault was as hopeless as the two first.

Besides this, the day's failure apparently spelt ruin to them ;

reinforcements from Augsburg were on their way to join us, and

certainly would have had time to arrive by nightfall, when the enemy

would find themselves in a very awkward position owing to the

demoralising effect of the woods and defiles to be repassed in the

retreat.

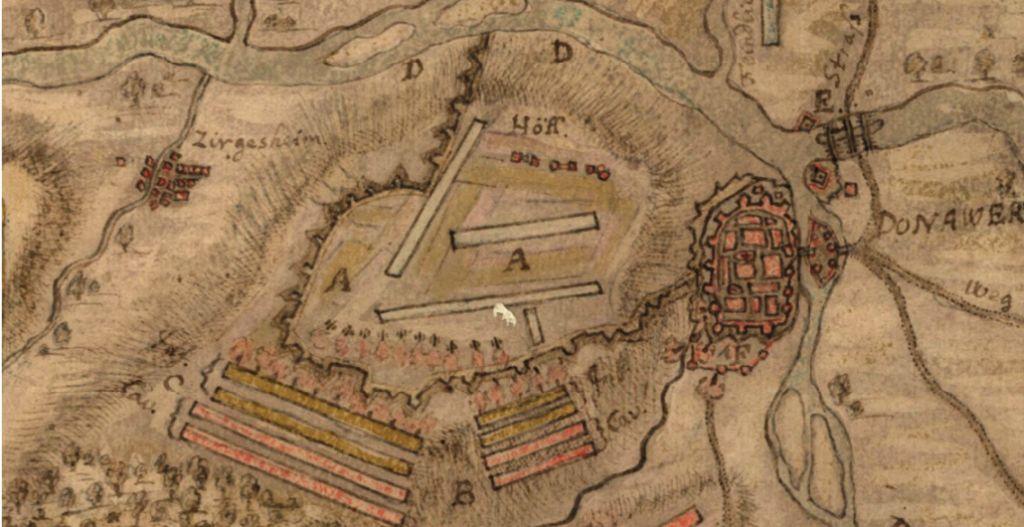

Contemporary

depiction of the attack on Schellenberg Heights (upper

left).Donauworth is shown in the centre and its suburbs burn to the

upper right. (Wiki)

France

would have then been able to carry out her original plan of

campaign, particularly as the enemy had already lost nearly fourteen

thousand men, as I learned from them- selves later on, a number that

would, as far as could be judged, be largely increased during a

forced retreat. But as it happened, matters had a different ending.

When the enemy found themselves safe from attack on the town side,

they hastened to make the most of the daylight left to them. It was

nearly seven in the evening when they began their movement to turn

this flank, which they did without making any change in their order

of battle. They had merely to turn their column to the flank, and by

reason of the fall of the ground, succeeded in changing their

position to their right, near the glacis, without meeting any

obstacle, or being seen by us. If we only could have been informed

of this movement, we could have moved to any place at which they

might have presented themselves, but we never believed it possible

that they would approach from this direction ; on the contrary, we

had been absolutely assured of the safety of this point, and seeing

no signs of a renewed assault, as the day waned, looked upon the

victory as ours, and, in fact, never was joy greater than our own

than at the very moment when we were in the greatest danger.

We

pictured to ourselves all the advantages produced by our successful

resistance, and the glory of the action itself, perhaps the most

memorable in the history of the world ; for after all, although the

enemy might in the end, as I shall show later on, find themselves

masters of our entrenchments, it could not diminish the glory due to

our ten battalions, for having sustained, unbroken, two determined

assaults of a formidable army, which after five hours' fighting no

longer dared to make even an appearance.

If

this action had been described in' detail by a practised hand, it

would be the subject of the admiration of the century, but however

good my own intentions in making a vivid and touching description of

it might be, I could not give effect to them, because my literary

powers would not be equal to the task. I shall content myself,

therefore, by remarking that our ten battalions, with hardly the

pretence of an entrenchment, held their own at Donauwort against the

violent and reiterated efforts of a whole and powerful army, which

five weeks later defeated, on the plain of Hochstett, the combined

forces of France and Bavaria, in which battle none of our battalions

took part. I leave the appreciation of the valour of our troops to

those who read these memoirs, and those more curiously inclined who

have studied the subject in other histories, to draw their own

deductions. I should not know how to set about it, for I declare,

before God and man, that I have never read any treatise on this war

except one regarding the Belgrade affair, in a book entitled The

Campaigns of Prince Eugene which one of my friends brought my wife,

as it contained a paragraph or so concerning me. I would go further

by saying that owing to the dislike I have always had of speaking of

war itself, I wrote these memoirs under a species of compulsion, and

would never have done so had I had my own way in the matter.

Detailed German

map showing the various positions including the location of the

pontoon bridge

escape route to the right across the Danube near Donauworth (Library

of Congress)

The

enemy then, having found means to change their position and their

line of attack unobserved, formed up on a broader front than before,

and advanced to attack part of the entrenchments guarded only by the

regiment of Nettancourt. This regiment, which was strung out in

single rank, was in no wise in a position to offer a serious

resistance, and retired into the town on their approach without

giving the slightest information of their movement to our ten

battalions. Our dragoons, who saw all this going on, came into

action, but a volley from the enemy killed so many of them that they

were obliged to retire without any possibility of their approaching

the angle we were holding. Maréchal d'Arcko and Major-General M. de

Liselbourg, who were at this point when the enemy broke through,

were also cut off from us, and never doubting but that our ten

battalions had already retired, made their way to the town, which

they had some difficulty in entering, owing to the hesitation of the

commandant to open the gates.

We,

however, remained steady at our post; our fire was as regular as

ever, and kept our opponents thoroughly in check. But while we were

thus devoting our attention to our own part of the field, the enemy

had possessed themselves of all the entrenchments on our left, and

shut us off completely from any communication with the town, which

ought at least to have served us as a haven of retreat. I was the

only commanding officer left among the ten battalions, and I had a

far from pleasing prospect before me.

Maréchal d'Arcko and Major-General Liselbourg had vanished, and

Count Emanuel d'Arcko, who had just been wounded, was drowned during

the retreat. He was colonel of the Prince Electoral's regiment, and

his lieutenant-colonel, M. de Mercy, had been sent to Italy ; the

latter's brother, the Chevalier de Mercy, lieutenant-colonel of the

guards, was also wounded, as well as the officer commanding the

Liselbourg regiment. Thus, I was left alone at the head of a body of

men full of pluck and confidence, but about to be deserted by

Fortune.

Although the enemy were in possession of all the entrenchments on

our left, they took, out of respect for us, every precaution when

advancing to attack us. As fast as the infantry entered the

position, their generals formed them up four lines in depth, and

although we now were lining our parapet and had our left flank at

their mercy, we had inspired them with such fear of our powers that

they advanced upon us in slow time with shouldered arms, either as

if to warn us it was time to retire, or because they still felt that

our aspect was too dangerous a one to risk anything rash.

What

made our position still more trying was that taking us thus in flank

they caught us, as in a trap, between their main line of battle and

the entrenchment which faced the wood on our right. However, to our

great good fortune, they never thought of dividing their force when

they had got into the entrenchments, and sending one portion to cut

off our retreat, whilst the other pressed us on the flank.

They

arrived within gunshot of our flank, about 7.30 in the evening,

without our being at all aware of the possibility of such a thing,

so occupied were we in the defence of our own particular post and

the confidence we had as to the safety of the rest of our position.

But I

noticed all at once an extraordinary movement on the part of our

infantry, who were rising up and ceasing fire withal. I glanced

around on all sides to see what had caused this behaviour, and then

became aware of several lines of infantry in greyish white uniforms

on our left flank. From lack of movement on their part, their dress

and bearing, I verily believed that reinforcements had arrived for

us, and anybody else would have believed the same. No information

whatever had reached us of the enemy's success, or even that such a

thing was the least likely, so in the error I laboured under I

shouted to my men that they were Frenchman, and friends, and they at

once resumed their former position behind the parapet.

|

"the

front of my jacket was so deluged with the blood which

poured from [my wound] that several of our officers

believed that I was dangerously hurt." |

Having, however, made a closer inspection, I discovered bunches of

straw and leaves attached to their standards, badges the enemy are

in the custom of wearing on the occasion of battle, and at that very

moment was struck by a ball in the right lower jaw, which wounded

and stupefied me to such an extent that I thought it was smashed. I

probed my wound as quickly as possible with the tip of my finger,

and finding the jaw itself entire, did not make much fuss about it ;

but the front of my jacket was so deluged with the blood which

poured from it that several of our officers believed that I was

dangerously hurt. I reassured them, however, and exhorted them to

stand firmly with their men. I pointed out to them that so long as

our infantry kept well together the danger was not so great, and

that if they behaved in a resolute manner, the enemy, who were only

keeping in touch with us without daring to attack us, would allow us

to retire without so much as pursuing. In truth, to look at them it

would seem that they hoped much more for our retreat than any chance

of coming to blows with us.

Marlborough

sending orders while enemy cavalry attack infantry in the

background. De Colonie notes the arrival of the Imperial Army who he

initially mistaken as French reinforcements. Several Austrian, Dutch

and Danish units wore a similar uniform as the French. When the

Imperial troops broke through outflanking the entrenched Bavarians,

an attempt was made to check the Imperial advance. It failed.

I at

once, therefore, shouted as loudly as I could that no one was to

quit the ranks, and then formed my men in column along the

entrenchments facing the wood, fronting towards the opposite flank,

which was the direction in which we should have to retire. Thus,

whenever I wished to make a stand, I had but to turn my men about,

and at any moment could resume the retirement instantaneously, which

we thus carried out in good order. I kept this up until we had

crossed the entrenchments on the other flank, and then we found

ourselves free from attack. This retreat was not made, however,

without loss, for the enemy, although they would not close with us

when they saw our column formed for the retirement, fired volleys at

close range into us, which did much damage.

My men

had no sooner got clear' of the entrenchments than they found that

the slope was in their favour, and they fairly broke their ranks and

took to flight, in order to reach the plain that lay before them

before the enemy's cavalry could get upon their track. As each ran

his hardest, intending to reform on the further side, they

disappeared like a flash of lightning without ever looking back, and

I, who was with the rear guard ready to make a stand if necessary

against our opponents, had scarcely clambered over the entrenchments

when I found myself left entirely alone on the height, prevented

from running by my heavy boots.

I

looked about on all sides for my drummer, whom I had warned to keep

at hand with my horse, but he had evidently thought fit to look

after himself, with the result that I found myself left solitary to

the mercy of the enemy and my own sad thoughts, without the

slightest idea as to my future fate. I cudgelled my brains in vain

for some way out of my difficulty, but could think of nothing the

least certain; the plain was too wide for me to traverse in my big

boots at the necessary speed, and to crown my misfortunes, was

covered with cornfields. So far the enemy's cavalry had not appeared

on the plain, but there was every reason to believe that they would

not long delay their coming ; it would have been utter folly on my

part to give them the chance of discovering me embarrassed as I was,

for as long as I was hampered with my boots, a trooper would always

find it an easy affair to catch me.

Cavalry attack fleeing troops. When the Cavalry

was unleashed on the fleeing Bavarians, no quarter was expected or

given..

The English and Imperial horse battle cry was "Kill, Kill and

Destroy" and they were true to their word.

I

noticed, however, that the Danube was not so very far away, and

determined to make my way towards it at all risk, with the hope of

finding some beaten track or place where there would be some chance

of saving my life, as I saw it was now hopeless to think of getting

my men together. As a matter of fact, I found a convenient path

along the bank of the river, but this was not of much avail to me,

for, owing to my efforts and struggles to reach it through several

fields of standing corn, I was quite blown and exhausted and could

only just crawl along at the slowest possible pace.

On my

way I met the wife of a Bavarian soldier, so distracted with weeping

that she travelled no faster than I did. I made her drag off my

boots, which fitted me so tightly about the legs that it was

absolutely impossible for me to do this for myself. The poor woman

took an immense time to effect this, and it seemed to me at least as

if the operation would never come to an end. At last this was

effected, and I turned over in my mind the best way to profit by my

release, when, raising my head above the corn at the side of the

road, I saw a number of the enemy's troopers scattered over the

country, searching the fields for any of our people who might be

hidden therein, with the intention, doubtless, of killing them for

the sake of what plunder might be found upon them. At this cruel

prospect all my hopes vanished, and the exultation I felt at my

release from the boots died at the moment of its birth.

My

position was now more perilous than ever ; nevertheless, I examined

under the cover afforded by the corn the manoeuvres of these

cavaliers to see if I could not find some way out of the difficulty.

A notion came into my head which, if it could have been carried out,

might have had a curious ending. It was that if one trooper only

should approach me, and his comrades remained sufficiently distant,

I should keep hidden and wait until he got near enough for me to

kill him with a shot from my pistol, for I had two on my belt ; I

would then take his uniform, mount his horse, and make my escape in

this disguise, a plan which would be favoured by the approaching

darkness. But not seeing any chance of being able to carry out this

idea, I thought of another, namely, to get into the river up to my

chin in the water under the bushes on the bank, wait for nightfall

and the return of the troopers to their camp, and then to escape in

the dark. But there were more difficulties to contend with in

risking this even than in the other case, and as a last resource it

struck me I might save myself by crossing the river, for happily I

knew how to swim, although the risk here was very great owing to the

breadth and rapidity of the Danube.

I

hurriedly determined on this plan, as I now saw a number of troopers

approaching ever nearer to my hiding-place, who were refusing to

give quarter to the unhappy wounded they found hidden in the corn,

whom they ruthlessly despatched the more easily to despoil them.

There was no reason to suppose that they were likely to show any

more mercy to me, particularly as I was worth more in the shape of

plunder than a private soldier, nor was there time to lose in making

up my mind, so I then and there determined to swim the river. Before

taking to the water I took the precaution of leaving on the bank my

richly embroidered uniform, rather spoiled as it was by the events

of the late action. I scattered in a similar manner my hat, wig,

pistols, and sword, at one point and another, so that if the

troopers came up before I had got well away, they would devote their

attention to collecting these articles instead of looking in the

water, and it turned out just as I thought. I kept on my stockings,

vest, and breeches, simply buttoning the sleeves of the vest and

tucking the pockets within my breeches for safety; this done, I

threw myself upon the mercy of the stream.

I had

hardly got any distance when up came the troopers, who, as I had

hoped, dismounted as quickly as they could to lay hands on the spoil

lying before them ; they even set to work to quarrel over it, for I

distinctly heard them shouting and swearing in the most delightful

manner. Others apparently got no share, and they amused themselves

by saluting me with several musket shots, but the current of the

river which carried me on my way soon put me out of their range.

Finally, after a very long and hard swim, I was lucky enough to

reach the other bank, in spite of the strength of the stream.

When I

had left the water and with it all anxiety regarding the safety of

my life, I suddenly found myself completely overcome with

exhaustion."